Royal Navy

Administration

The Royal Navy and the Naval Service as a whole was directed by the Board of Admiralty, composed of a political appointee styled the First Lord of the Admiralty who represented the Navy in Cabinet and in Parliament. He was advised by a number of naval officers on the Board with variously defined briefs. The First Lord's chief adviser was the First Sea Lord (before 1904 known as the First Naval Lord) who was responsible for the fighting efficiency of the fleet. The Second Sea Lord (formerly Second Naval Lord) was responsible for personnel. The Third Sea Lord (also known as Controller of the Navy) was responsible for matériel. The Fourth Sea Lord (previously known as the Junior Naval Lord) was responsible for supplies. Also on the Board was another politician with the office of Civil Lord of the Admiralty. An Additional Civil Lord was added in 1912. Quorum for the Board was two members, and it issued its directives through the Permanent Secretary to the Board of Admiralty, a civil servant, who was not a member of the Board. Another official who was not a member was another political appointee, the Parliamentary and Financial Secretary.

The "Admiralty" was a term which encompassed the Admiralty buildings in London housing the various departments which ran the Navy; the Department of the Secretary, the Hydrographic Department which mapped the world's oceans, the Naval Intelligence Department created in 1889, the Department of the Director of Naval Ordnance and Torpedoes, the Department of the Director of Naval Construction, the Department of the Engineer-in-Chief (the latter three formerly being in the Department of the Controller), the Department of the Medical Director-General, the Department of the Director of Transports, the Department of the Accountant-General, the Contract and Purchase Department, Victualling Department, the Office of the Admiral Superintendent of Naval Reserves (later the Office of the Admiral Commanding Coastguard and Reserves) and the Royal Marine Office.

The Naval Intelligence Department in the early years of the Twentieth Century effectively became a naval staff which advised the Board of Admiralty on dispositions and strategy. In 1911 this informal arrangement was replaced by the institution of the Admiralty War Staff under a Chief of the Staff which reported to the Board of Admiralty, but was still only advisory. In 1917 the staff became the Naval Staff and was given executive powers, the First Sea Lord becoming Chief of the Naval Staff, and two new appointments tasked with administering the Staff, the Deputy Chief of the Naval Staff and Assistant Chief of the Naval Staff, were given positions on the Board. Also in 1917 a Fifth Sea Lord was appointed to represent the Royal Naval Air Service, although with the creation of the Royal Air Force in 1918 this position was discontinued. From 1917 to 1918 the position of Controller, discontinued in 1912, was revived to be held by civilians and made responsible for shipbuilding and production. At the Armistice the office was merged with that of Third Sea Lord.

Fleets

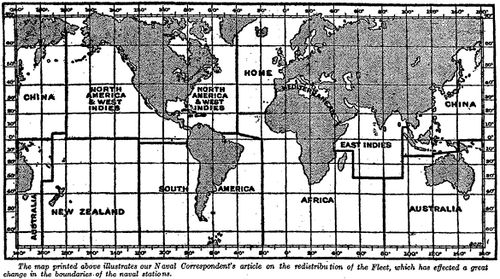

At the end of the nineteenth century the main British fleet was in the Mediterranean, based on Malta. This fleet controlled the main contestable sea route to the Indian Empire. In Home waters was the Channel Squadron, as well as ships in reserve at the Home Ports. Smaller squadrons under Commanders-in-Chief were maintained on the North America and West Indies Station, the Cape of Good Hope Station, the China Station, Australia and the West Coast of America. In 1904 Admiral Sir John Fisher, one of the most prominent sailors in British history, claimed that, "Five keys lock up the world! Singapore. The Cape. Alexandria. Gibraltar. Dover."[2] All these locations, of course, fell within British spheres of influence and control.

When Fisher became First Sea Lord at the end of 1904, a redistribution of the fleets began to concentrate ships in Home waters and to save money having ships on overseas stations. Battleships were removed from the China Station. A recently created South American squadron was disbanded. The Pacific Station had already been done away with. The North America Station was reduced to a cruiser squadron. In 1903 a sea-going Home Fleet had been formed out of the reserves in addition to the Channel Squadron. In 1904 the former became the Channel Fleet and the latter became the Atlantic Fleet, both powerful battleship squadrons with attached cruiser squadrons. In 1907 a new Home Fleet was formed, composed of three divisions at the Home Ports. This squadron rapidly became the Royal Navy's main fleet. The Channel Fleet was absorbed into it in 1909, and the Atlantic Fleet in 1912.

In 1912, the Mediterranean Station lost its battleships, and the fleet in Home waters became the Home Fleets under one Commander-in-Chief. It was organised into three fleets; the First being composed of fully-manned warships, and the Second and Third Fleets under a Vice-Admiral were composed of ships manned by nucleus crews which would be brought up to strength by active service ratings and reservists, respectively. Battleship and cruiser squadrons were commanded by Vice-Admirals and Rear-Admirals respectively, while an officer was placed in command of the fleet's destroyers. An Admiral of Patrols was appointed in 1912 to administer the local defence destroyer flotillas on the East Coast of Great Britain. Destroyers and submarines had from 1905 to 1907 been under the operational command of a Rear-Admiral, but from then on operationally and administratively submarines came under the Inspecting Captain of Submarines.

Dockyards and Reserves

At the turn of the century the three main ports in Home waters were Portsmouth, Plymouth (Devonport) and Chatham. These were the so-called manning ports, with ratings assigned to a port and then a ship was normally crewed by men from one port, hence "H.M.S. So-and-so was a Chatham ship" meant she was a ship crewed with men from Chatham. Each of the Home ports came under the authority of a Commander-in-Chief, usually a senior flag officer. The second-in-command of the Port was the Admiral Superintendent of the port's Dockyard, normally a Rear-Admiral. The Admiral Superintendent was responsible for the administration of the dockyard.

Personnel

Officers

Officers of the Royal Navy were divided into "Branches." Executive command was vested in officers of the Military Branch (Royal Navy). Initially all other commissioned officers were placed in a "Civil" branch which was further sub-divided into specialist branches as the Nineteenth Century wore on. Until 1915 the Military Branch was delineated by the "curl" above the distinguishing lace, whilst the other branches were differentiated by different colours between the lace.

Military Branch

Traditionally officers of the military branch were entered as boys, although this was supplemented in 1913 by the introduction of the Special Entry scheme which allowed boys of school leaving age to enter the Royal Navy. Up to 1903 boys wishing to join as officers had to obtain a nomination, either from an officer qualified to grant one or from the First Lord of the Admiralty. Having obtained a nomination the boy then had to pass an examination. If he passed he then became a Naval Cadet. Before 1857 naval cadets were sent direct to sea. After 1857 they were educated in a training ship for a maximum of two years; first in the Illustrious, and then the Britannia in 1859, moored first at Portsmouth, Portland, and then Dartmouth in 1863, where practically all naval cadets received their initial training until 1905. With the introduction of the Selborne Scheme in 1903, Naval Cadets were entered by means of competitive examination and an interview by a special panel. They then were educated for two years at the Royal Naval College, Osborne, and two years at the Royal Naval College, Dartmouth.

Engineer Branch

Medical Branch

Accountant Branch

Ratings

See Also

Footnotes

Bibliography

- Kafka, Roger; Pepperburg, Roy L. (1946). Warships of the World—Victory Edition. Ithaca, NY: Cornell Maritime Press.

Recommended Reading

- Brown, David K, RCNC (2003). Warrior to Dreadnought: Warship Development 1860 — 1905. London: Chatham Publishing. (on Amazon.com and Amazon.co.uk).

- Brown, David K, RCNC (1999). The Grand Fleet: Warship Design and Development 1906 — 1922. London: Chatham Publishing. (on Amazon.com and Amazon.co.uk).

- Clowes, William Laird (1897). The Royal Navy: A History From the Earliest Times to the Present. Vol. VII. London: Sampson Low, Marston and Company.

- Marder, Arthur J. (1964). The Anatomy of British Sea Power: A History of British Naval Policy in the Pre-Dreadnought Era, 1880—1905. London: Frank Cass & Co., Ltd.. (on Amazon.com and Amazon.co.uk).

- Marder, Arthur J. (1961). From the Dreadnought to Scapa Flow, The Royal Navy in the Fisher Era, 1904-1919: The Road to War, 1904-1914. Volume I. London: Oxford University Press.