114th Meeting of the Committee of Imperial Defence

The 114th Meeting of the Committee of Imperial Defence took place on 23 August, 1911.[1] According to historians Steiner and Neilson “this was to be the only time that the CID actually reviewed the overall pattern of British strategy before 1914”.[2] The Royal Navy’s presentation at the meeting, and Admiral of the Fleet Sir Arthur K. Wilson in particular, has generally been ridiculed in the historiography—Steiner and Neilson, for example, refer to “the glaring incompetence of the navy”[3]—but has recently (2015) been re-examined by Morgan-Owen, who concluded that “the naval portion of his [Wilson’s] strategy … was far more credible than has hitherto been appreciated”.[4]

Minutes

The Right Hon. D. LLOYD GEORGE, M.P., Chancellor of the Exchequer. The Right Hon. SIR EDWARD GREY, Bart., M.P., Secretary of State for Foreign Affairs. The Right Hon. W. S. CHURCHILL, M.P., Secretary of State for the Home Department. The Right Hon. REGINALD MCKENNA, M.P., First Lord of the Admiralty. Admiral of the Fleet SIR ARTHUR WILSON, G.C.B., G.C.V.O., V.C., First Sea Lord of the Admiralty. Rear-Admiral the Hon. A. E. BETHELL, C.M.G., Director of Naval Intelligence. The Right Hon. VISCOUNT HALDANE, Secretary of State for War. Field-Marshal SIR WILLIAM NICHOLSON, G.C.B., Chief of the Imperial General Staff. Brigadier-General H. H. WILSON, C.B., D.S.O., Director of Military Operations. General SIR JOHN FRENCH, G.C.B., G.C.V.O., K.C.M.G., Inspector-General of the Forces. Rear-Admiral SIR CHARLES OTTLEY, K.C.M.G., C.B., M.V.O., Secretary. Major-General SIR A. J. MURRAY, K.C.B., M.V.O., D.S.O., Director of Military Training, also attended. |

||

| THE PRIME MINISTER said he had called the Committee together as the European situation was not altogether clear, and it was possible that it might become necessary for the question of giving armed support to the French to be considered. | ||

| The Sub-Committee which examined this question in 1908 came to the following conclusions:— | Report of Sub-Committee on “Military needs of the Empire (C.I.D. Paper 109-B).[”] | |

| “(a) The Committee, in the first place, desire to observe that, in the event of an attack on France by Germany, the expediency of sending a military force abroad or of relying on naval means alone is a matter of policy which can only be determined when the occasion arises by the Government of the day. | The question of policy. | |

| “(b) In view, however, of the possibility of a decision by the Cabinet to use military force, the Committee have examined the plans of the General Staff, and are of opinion that, in the initial stages of a war between France and Germany, in which the Government decided to assist France, the plan to which preference is given by the General Staff is a valuable one, and the general Staff should accordingly work out all the necessary details.” | Instructions to the General Staff. | |

| The General Staff had prepared a fresh Memorandum on the subject in the light of recent developments (C.I.D. Paper 130-B), and on the second hypothesis that the United Kingdom becomes the active ally of France, the important points were those contained on p. 2, namely, that we should mobilise and dispatch the whole of our available regular army of six divisions and a cavalry division immediately upon the outbreak of war, mobilising upon the same day as the French and Germans. It was further suggested that additional reinforcements, consisting of two or three divisions of British and native troops might be drawn from India, and possibly the seventh division from the Mediterranean and South Africa. | Re-examination of the question by the General Staff. Proposals of the General Staff. | |

| Lastly, the General Staff asked from the Admiralty an assurance that the Expeditionary Force could be safely transported across the Channel and from the other directions indicated in their paper, and that the Navy will protect the United Kingdom from organised invasion from the sea. As regards these last two points, Admiralty Memorandum (C.I.D. Paper 131-B) did not give a categorical reply. |

Assurances asked from the Admiralty by the General Staff. | |

| SIR ARTHUR WILSON said that the reply of the Admiralty to the first question was that the Navy could spare no men, no officers, and no ships to assist the Army. The whole force at the disposal of the Admiralty would be absorbed in keeping the enemy within the North Sea. Ordinarily the Navy would furnish transport officers and protecting ships. These could not be furnished in these circumstances. The Channel would, however, be covered by the main operations, and provided the French protected the transports within their own harbours, the Admiralty could give the required guarantee as too the safety of the expedition. | Inability of the Navy to assist. Safety of the expedition guaranteed. | |

| SIR WILLIAM NICHOLSON said that as regards that point the General Staff asked for no more. He presumed that the General Staff could count upon the ungrudging support of the Transport Department of the Admiralty. | ||

| MR. MCKENNA said that assistance could not be given during the first week of war. The whole efforts of the Admiralty weould be absorbed in mobilising the Navy, and the Transport Department especially would be fully occupied in taking up Fleet Auxiliaries. | Transport Department of the Admiralty unable to assist during the first week of war. | |

| SIR WILLIAM NICHOLSON said that the whole scheme had been worked out in detail. He also pointed out that in the Russo-Japanese war, the Japanese Navy had handed over the whole business of sea transport over to the military authorities, who carried out the work without difficulty. | ||

| MR. MCKENNA said that the difficulty lay in the question of time. | ||

| ADMIRAL BETHELL said that the demands of the army could not be attended to if they were simultaneous with the mobilisation of the Fleet. | ||

| MR. MCKENNA said that he heard of this scheme now for the first time. | The General Staff proposals not previously communicated to the First Lord. | |

| SIR WILLIAM NICHOLSON said that in accordance with the conclusion arrived at by the Sub-Committee, as set out in paragraph 20 (b) of their report dated the 24th July, 1909 (C.I.D. Paper 109-B) the General Staff had worked out the details of the scheme with the Departments of the Admiralty concerned. The Director of Naval Intelligence had laid down that to ensure the safety of the transports their courses must be west of a line drawn from Dungeness to Cape Griz Nez. The sea transport of the force had been worked out with the Director of Transports in detail day by day. Such a scheme necessarily implied war. | The plans worked out in detail by the General Staff with the Naval Intelligence and Naval Transport Departments in accordance with the instructions of the C.I.D. | |

| MR. MCKENNA said that the question was whether the Director of Transports understood that the resources of his Department were to be called upon for the dispatch of the Army simultaneously with the mobilisation of the Fleet. The date at which this operation was to take place and the length of time it would require were the essential points. The Admiralty could not undertake the two operations simultaneously. | The Naval Transport Department unable to cope with simultaneous naval and military demands. | |

| GENERAL WILSON asked if that opinion held good even if every detail had been worked out beforehand. | ||

| ADMIRAL BETHELL said that he had not been able to see Admiral Groome, the Director of Transport [sic], but he understood from his Department that they had assumed that the Fleet had already been mobilised. | ||

| SIR ARTHUR WILSON said that the scheme had not been brought to his notice. He had understood that a scheme for dispatching the Expeditionary Force had been mooted, but that it had been abandoned. | The First Sea Lord unaware of the scheme. | |

| MR. MCKENNA said that there was no question as to the safety of the transports, the sole difficulty was the question of time and the simultaneous demand upon the Transport Department of the Admiralty to meet naval and military requirements. | The question one of time, not of safety. | |

| THE PRIME MINISTER said that the plans of the General Staff as laid before the Sub-Committee of 1908 had always laid stress on the necessity for mobilisation and concentration taking place immediately upon the outbreak of war, if military intervention was to be valuable, and he was at a loss to understand why it should be supposed that the Fleet should not be mobilising at the same time. | Time always an essential feature of the General Staff proposals. | |

| MR. MCKENNA said that the Admiralty had actually recorded in a C.I.D. Paper their inability to guarantee the transport of troops upon the outbreak of war. | Formal record by the Admiralty of their inability to transport troops on the outbreak of war. | |

| THE PRIME MINISTER read the paragraph referred to in C.I.D. Paper 116-B as follows:— (1). The general principle which has for many years governed the question of reinforcements is that the movement of troops by sea in the early days of a maritime war is an operation attended with serious risk, and the Admiralty cannot guarantee to protect the transports so employed. This did not appear to him to have reference to the present case in which the question was one of ferrying troops over narrow waters to a friendly country, and he was surprised that the Admiralty were not prepared to guarantee the safety of the transports. |

The principle inapplicable to the present case. | |

| MR. LLOYD GEORGE enquired whether we could not count also upon the co-operation of the French Fleet. | Co-operation of the French Fleet. | |

| MR. MCKENNA said that almost the entire French Fleet was in the Mediterranean. | ||

| MR. CHURCHILL enquired whether there was not some risk of German war vessels outside the North Sea interfering with the transports, if all our ships were employed in shutting the Germans in and none were left to patrol the Channel. | ||

| SIR ARTHUR WILSON said that the risk was very slight. Up to the fifth or sixth day after the declaration of war we should have ships traversing the Channel on the way to their stations. This would give some local protection in addition to that afforded by the main operation. | Risk of hostile interference with the expedition very slight. | |

| LORD HALDANE said that the real point seemed to be the question of transports. Could the Admiralty carry out the scheme as worked out or not. | ||

| GENERAL WILSON said that the dates fixed for embarkation to begin were from the second day of mobilization up to the twelfth day. He certainly imagined that the Director of Transport understood. | ||

| MR. MCKENNA said that the First Sea Lord would examine into the questions raised. He regretted that there should have been any misunderstanding. | Admiralty to examine the question. | |

| THE PRIME MINISTER said that it was necessary that it should be understood that the question of time was all important. The simultaneous mobilisation of our army and that of the French, and the immediate concentration of our army in the theatre of war were essential features of the scheme. The second assurance asked for by the General Staff, that of a guarantee by the Admiralty against invasion might be postponed for the moment, and he would first ask the Committee to consider the desirability of carrying out the operations proposed by the General Staff or the alternative scheme suggested by the Admiralty on their merits. |

The question time all-important. | |

| GENERAL WILSON said that our Expeditionary Force consisted of— 1 Cavalry Division; 6 Divisions; Army Troops; a total of about 160,000 men. |

Strength of the British Army. | |

| Continuing, he referred to a large-scale map and stated that for the purposes of war Luxembourg might be regarded as German and that there was no reason to suppose that Germany would not hesitate to march through Southern Belgium. | Disregard of the neutrality and Belgium and Luxembourg. | |

| The Franco-German frontier might therefore be taken as extending from Altkirch to Aix-la-Chapelle (Aachen) on the one side and from Belfort to Maubeuge on the other. A distance in each case of about 230 miles. The former places could be taken as indicating the line upon which the Germans must detrain their troops and from which they must march. | Line of the German deployment. | |

| On the French side this 230 miles of frontier was closed by lines of fortresses and connecting works. The southern line extending from the fortress of Belfort, which commanded the country up to the Swiss frontier, to Epinal. From Epinal there was an unfortified gap of 30 miles to Toul, and from Toul a second fortified line stretched north for 60 miles to Verdun, beyond which 90 miles of open frontier extended to Maubeuge. The fortresses named were modern and strongly fortified. Beyond Maubeuge and there was the fortress of Lille, also strong. La Fère and Laon were being dismantled and Rheims was half-open. Paris itself was very strongly fortified. In the south Langres, Dijon and Besançon were all strong, modern fortresses. The garrisons of the frontier defences amounted to about 250,000 men, the garrison of Paris to 250,000, and other garrisons brought the total to about 600,000 men. Rheims was only weakly garrisoned. The 30-mile gap between Epinal and Toul contained only four roads running through difficult country, and this gap was defended by a French Army based upon Langres. None of the French fortresses could be taken otherwise than by siege operations. The connecting works (“forts d’arrêts”) might possibly be taken by assault. The German fortresses, with the exception of Metz, were situated on the Rhine. Metz had been very strongly fortified in recent years and was now second only to Paris in Strength. |

||

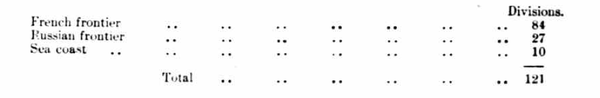

The total number of German divisions which could be considered as mobile and able to take and keep the field has been estimated at 121. These would probably be distributed as follows:— In present circumstances, he thought that 84 divisions the limit of a German Army invading France. |

Strength of the German Army. | |

| Against this force the French could put 75 divisions, less 9 required to watch the Italian frontier, or a net total of 66 divisions. To these must be added, say, 200,000 fortress troops, who could take a share in the defence of the line of the Meuse. | Strength of the French Army. | |

| SIR EDWARD GREY said that he did not think that the French would have anything to fear from Italy. | Influence of Italy. | |

| GENERAL WILSON said that however that might be, there was no doubt that in the first deployment, the French would employ nine division to watch the Italian frontier. The French fortified lines were probably safe against attack, and, as he had already indicated, the gap between Epinal and Toul did not form a favourable line of advance. The German would, of course, attack all along the line, but their main effort must be made through the 90-mile gap between Verdun and Maubeuge. Through this gap there ran only thirteen through roads. Each road could accommodate three divisions, but not more. So that the limit of numbers which the Germans could employ along this front was about 40 divisions. A similar result was arrived at upon the basis of the extent of front upon which a division could fight, namely from 2 to 2¼ miles. |

Strength of the German main attack. | |

| Against this force the French could probably place from 37 to 39 divisions. So that it was quite likely that our six divisions might prove to be the deciding factor. | Strength of the French active defence. Effect of the intervention of the British Army. | |

| MR. MCKENNA enquired how it was possible for the French and British forces to oppose a greater number of divisions to the Germans in view of the limitations of 3 divisions to a road. | ||

| GENERAL WILSON said that it was owing to the French having their own railways to supply them. Railways would not available to the Germans in the earlier stages. | ||

| MR. CHURCHILL asked whether the Germans might not extend their right further into Belgium. GENERAL WILSON said that to do this the Germans must either infringe the neutrality of Holland or take Liege. This fortress was strong, but normally its garrison was very weak—700 to 1,000 men—which was quite inadequate to defend it. It was possible, therefore, that the Germans might take it by a coup de main. But they could not hope to capture Huy or Namur or Antwerp in the same way. That portion of their force advancing along the left bank, that is north, of the Meuse would accordingly have to guard its right against the fortress of Antwerp, and if it had entered Belgium through Dutch territory without having captured Liege, it would have to mask that fortress, while in its further advance it would be separated from it main body by the fort of Huy, the fortress of Namur and by the River Meuse. This would be dangerous. Moreover, although the Belgians would possibly be content to protest against the violation of their southern provinces, they would almost certainly fight if the Germans were to invade northern Belgium as well. The Belgian field army would number 80,000 men. |

Extension of the German right to the left bank of the River Meuse. | |

| On the whole front the broad result was that, although the Germans could deploy 84 divisions against the French 66 and the garrisons of their frontier fortresses, the Germans could not concentrate their superior force against any one point. Our 6 divisions would therefore be a material factor in the decision. Their material value, however, was far less than their moral value, which was perhaps as great as an addition of more than double their number of French troops to the French Army would be. This view was shared by the French General Staff. | Value of the intervention of the British Army. | |

| SIR EDWARD GREY agreed that our military support would be of great moral value to the French. As to the Belgians, he thought that they would avoid committing themselves as long as possible in order to try and make certain of being on the winning side. | ||

| MR. CHURCHILL enquired what force the Germans could bring up between Lille and Maubeuge by the fifteenth day, if they wished to do so. | German advance through Northern Belgium. | |

| GENERAL WILSON said that six through roads crossed the frontier between Lille and Maubeuge, but it was impossible to say without detailed examination of such a problem, in which so many indeterminate factors existed, what strength the Germans might attain to, and by date they could this line. If the Germans were to extend their front to the north in this manner the French would be able to bring up ten divisions from the south, perhaps more. | ||

| MR. CHURCHILL asked whether the Germans had not sufficient force to attack each gap and to march through Northern Belgium as well. | ||

| GENERAL WILSON said that that was so, but their difficulty was that the march through Northern Belgium was a dangerous operation, and would require so many men to mask the Belgian Army and the Belgian fortresses that if the figures were carefully examined, it would be found that in present circumstances no advantage and a good deal of risk would accrue to the Germans by taking this course. In ten years’ time they would have so many men that they certainly would be able to press their attack all along the line and march through Northern Belgium as well with additional divisions in reserve at rail head. | Future increase in strength of the German Army. | |

| SIR JOHN FRENCH said that he had always understood that the object which the German General Staff had in view when they decided to fortify Metz, was to enable them to send larger forces through Belgium to turn the French left. The war garrison of Metz was 70,000, and there were 51,000 men there in peace. Any French advance would now have to be made between the fortresses of Metz and Strasburg, and would no longer be worth while attempting. | German advance through Northern Belgium. | |

| MR. CHURCHILL said that it seemed to him that the Germans might wait until say the 20th day, or so long as required to assemble the necessary numbers, and then advance upon a broad front. He did not think that they need fear attack by the Belgians. | ||

| SIR JOHN FRENCH said that he was inclined to agree with Mr. Churchill. | ||

| GENERAL WILSON said that the Belgian Army, though small, could not be ignored, and its strategical position upon the German flank was strong. | Belgian Army not negligible. | |

| MR. LLOYD GEORGE said that he agreed. Even if the Belgians did not attack, while the Germans were advancing, the Germans were bound to make provision against their doing so, if the course of events should prove adverse to Germany. | ||

| SIR EDWARD GREY said that the greater the reserve manifested by the Belgians at the outset, the more nervouse would the Germans be as to their ultimate intentions. The German superiority in numbers would be counterbalanced to some extent by the disadvantage of fighting in the enemy’s country. |

||

| MR. MCKENNA added that the Germans would also be handicapped by their longer lines of communication. | ||

| MR. LLOYD GEORGE asked what advantage in point of numbers might be considered to ensue to the French owing to their being on the defensive. | ||

| SIR JOHN FRENCH said that it was impossible to answer Mr. Lloyd George’s question satisfactorily, as it depended upon so many factors. | ||

| SIR WILLIAM NICHOLSON said that in the case of the defence of a fortified position it might amount to as much as three to one; but otherwise it was impossible to say beforehand what, if any, advantage would lie with a force acting on the defensive. | ||

| GENERAL WILSON, replying to Lord Haldane, said that the country between Lille and Maubeuge was similar to the country round Birmingham. It was also worth noticing that there was not a single good road—there were roads—in the difficult piece of country between Givet and Mezières, so that troops moving north of this district would be separated from those moving south of it. | ||

| MR. LLOYD GEORGE asked whether the General Staff could forecast what would happen if the French were driven back from the line of the Meuse. | Situation ensuing upon a French retreat. | |

| MR. CHURCHILL said that it was important that this aspect of the case should be considered. | ||

| GENERAL WILSON said that it depended upon so many unknown factors that it was very difficult to prophesy what course the French might take, and he had no knowledge of what the views of the French General Staff on the subject were. One thing he thought was fairly certain and that was that the French Field Army would not retire towards Paris, but would base itself upon the richer southern provinces, leaving Paris to be defended by its own garrison of 250,000 men. As to the Germans, they would not invest Paris till they had disposed of the French Field Army. The garrison of Paris was immobile. The other French fortresses were only intended to break up the German advance. When the French Field Army was destroyed, the rest must follow, and France would be conquered. | ||

| SIR ARTHUR WILSON said that apart from the smallness of its numbers and other considerations, our Army would labour under disadvantages due to difference of language and training, and diversity of ammunition, arms, and equipment. It would also be handicapped by its dependence for its supplies upon French railways. In the early days of the war, when it was proposed to dispatch our forces, the French would also be mobilising, and there would be congestion on the railways. | Military co-operation with the French. | |

| SIR WILLIAM NICHOLSON said that the whole question of concentration, including sea and railway transport, and of supply, had been worked out, and he did not anticipate serious difficulty in these matters arising. | ||

| MR. CHURCHILL enquired when the concentration of the British Army would be finished. | ||

| GENERAL WILSON said that the last troop train was timed to reach the neighbourhood of Maubeuge at midnight on the 13th/14th day of mobilisation. | Date of the completion of a British concentration in the theatre of war. | |

| THE PRIME MINISTER asked what the relative quality of the French and German armies was supposed to be. GENERAL WILSON said that he would prefer to command a French Army rather than a German one. SIR JOHN FRENCH said that he agreed, but the Germans had a very great advantage in the personal influence of the Emperor. This was an asset which the French lacked. The Germans, too, were absolutely confident. The French were not equally so. |

Relative quality of the French and German Armies. | |

| LORD HALDANE said that the German Army was a perfect machine. | ||

| SIR WILLIAM NICHOLSON said that the over-confidence of the Germans would probably lead to very heavy losses. | ||

| SIR EDWARD GREY said that the French did not want war, but if it came they would fighting for their lives, and that they would realise. | ||

| MR. LLOYD GEORGE enquired as to the French leaders. | ||

| GENERAL WILSON said that so far as it was possible to judge in peace, they were good, and the staff was excellent. | ||

| MR. CHURCHILL said that he would like to return to the possibility of the French being forced to retire. What would then happen to our force at Maubeuge? | Situation ensuing on a French retreat. | |

| GENERAL WILSON said that the French Army would probably not retire upon Paris, but would base itself, as he had said, upon the south. Our command of the sea would enable us to change our base as we required. Reserve supplies sufficient for three months would in the first instance be collected at Amiens. | ||

| MR. CHURCHILL said that Amiens seemed to him rather far forward. It would not take the Germans long to reach that place after winning a battle on the line Lille-Maubeuge. | ||

| GENERAL WILSON said that it would take them much longer than would appear at first sight. The vast numbers in modern armies could not live upon the country, and at the utmost could not go more than 60 miles from their rail-head base. The railways, therefore, had to be got into working order, which might involve much delay. Granting everything favourable to the Germans their Army might cover this distance of 50 or 60 miles in fifteen or sixteen days, but it might take much longer—perhaps two months. | ||

| MR. LLOYD GEORGE asked whether the French arrangements for mobilisation were good. | ||

| GENERAL WILSON said that, so far as he knew, they were perfect. | ||

| MR. MCKENNA said that he did not think the German would hesitate to infringe Dutch neutrality as well as Belgian, if respect for it was inconvenient to their military operations. | Infringement of Dutch neutrality not improbable. | |

| GENERAL WILSON said that if the Dutch allowed the Germans to make use of their territory in furtherance of their operations of war, we could retaliate by blockading Dutch seaports. Such retaliation would also increase the economic pressure on Germany. | Blockade of Dutch and Belgian ports. | |

| SIR EDWARD GREY said that a threat to blockade Antwerp in the event of the Belgians allowing the Germans to infringe their neutrality unopposed might influence them to resist. | ||

| SIR ARTHUR WILSON said that by blockading Dutch and Belgian ports we should run the risk of throwing those countries into the arms of Germany. | Danger of blockading Dutch and Belgian ports. | |

| MR. LLOYD GEORGE enquired what the view of the Belgians was supposed to be. | The Belgian attitude. | |

| GENERAL WILSON said that roughly speaking one-half of the population favoured the Germans and the other half the French, but the whole nation would, he though, resent a German incursion north of the Meuse. | ||

| MR. CHURCHILL said that he was not yet clear as to the views of the General Staff upon the second phase of the campaign, which might ensue upon the retirement of the allies after a heavy action along the line of the Meuse. This phase was conceivable and appeared to him to be of great potential importance. The economic pressure upon Germany would be increasing and the Russian operations should be exercising some influence, but the events in the French theatre would still be the most important. What was to the action of the British Army on the French retirement. Would they follow the French and base themselves on the south or would they retire upon Paris and threaten the German communications. | Situation ensuing upon a French retreat. Action of the British Army in the event of a French retreat. | |

| GENERAL WILSON said that the unknown factors were so numerous that a certain reply could not be given. But we ought, undoubtedly, to retain touch with the French left. It must not be forgotten that behind the Field Army the Germans had no less than 800 battalions available for the defence of their communications. The pressure of the Russian Army would not amount to very much. They could only put forty effective divisions into the field, while Austria and Germany could meet these with fifty-seven. | German Reserves. Influence of Russia. | |

| SIR JOHN FRENCH said that assuming we were driven back, we always had the advantage that our command of the sea enabled us to change our base. It was, however, important to consider with whom the decision as to the future movements of the British force would lie. | ||

| GENERAL WILSON said that our Army retained absolutely its freedom of action, and that therefore the decision as to its subsequent operations would lie with our own Government. | The British Army to retain its independence. | |

| MR. CHURCHILL said that he did not like the idea of the British Army retiring into France away from its own country. | ||

| SIR WILLIAM NICHOLSON said that similar operations had often fallen to our lot before—for instance, under Marlborough. | ||

| MR. MCKENNA said that the conditions were not analogous. In his view, if a British force were sent at all, it should be placed under French command. | The British Army, if sent at all, should be under French command. | |

| GENERAL WILSON said that the General Staff could not accept this view. | Dissent from this view. | |

| MR. CHURCHILL dissented emphatically. The whole moral significance of our intervention would be lost if our Army was merely merged in that of France. In his view, in the circumstances contemplated, our proper course would be to withdraw west of Paris, where we should count for more than we should in the south. | Action of the British Army in the event of a French retreat. | |

| GENERAL WILSON said that the victorious Germans would detail a force two or three times the strength of our isolated detachment, which eventually could hardly fail to be surrounded. | ||

| MR. CHURCHILL said that we could always retreat to the sea. | ||

| MR. MCKENNA said that we should still be pursued by the victorious Germans. | ||

| MR. LLOYD GEORGE said that the campaign would then end, as did Sir John Moore’s at Corunna. | ||

| SIR JOHN FRENCH said that would could not be waged without risks. | ||

| MR. LLOYD GEORGE asked if our risks would be less if we maintained our connection with the French. | ||

| SIR WILLIAM NICHOLSON said that it was hardly possible to contemplate that immediately upon a retreat taking place, we should sever our connection with the French. We would be obliged to conform generally to the French movements. | ||

| SIR JOHN FRENCH said that he did not understand why it should be assumed that a gap between our Army, retiring along its own communications, and the French Army must inevitably occur. The French line of retreat might well lie more to the west than we had so far assumed. | ||

| MR. LLOYD GEORGE said that the point was, what course we were to pursue if the French did retire southwards. | ||

| GENERAL WILSON said that he did not pretend to know what the intention of the French might be. | ||

| MR. CHURCHILL suggested that it might be desirable to discuss the question with the French General Staff. | ||

| MR. MCKENNA expressed doubt whether such a question ought to be discussed with the French General Staff. | ||

| SIR EDWARD GREY agreed that its discussion was of doubtful desirability. In any case, he though that the first matter to settles was whether proposed action in the first phase of the campaign was practicable, and whether it was likely to achieve valuable results. He enquired when the first general action was calculated to take place. | ||

| GENERAL WILSON said that in all probability it would take place between the seventeenth and twentieth days after the French and German mobilisation were ordered. | Probable date of the first general action. | |

| MR. MCKENNA said that for that action it appeared that the Germans would have a maximum number of seventy divisions and the French would have sixty-six. The latter seemed to him to be ample with which to defend their frontier. Was the probable effect of our intervention with six divisions so great that without it the French would not resist German aggression, while with it they would. | Effect of the intervention of the British Army. | |

| SIR EDWARD GREY said that we must postulate that the French intended to fight. The point was whether our intervention would make the difference between defeat and victory. | ||

| MR. MCKENNA asked whether, if we gave the French an assurance of assistance now, it would not make the French less inclined to accept the German terms. | ||

| THE PRIME MINISTER said that the point which the Cabinet would have to decide was what we were going to do if we resolved to commit ourselves to the [sic] support the French against German attack. | ||

| LORD HALDANE said he thought the Committee were now acquainted with the probable effect of our military intervention. | ||

| MR. LLOYD GEORGE said that he would like further light thrown on the part Russia would play. The force which the General Staff calculated that the Russians concentrate upon their western frontiers seemed very small in comparison with the reputed numbers of their soldiers. What were their difficulties? Were they financial? | Influence of Russia. | |

| GENERAL WILSON said that there was no difficulty as regards finance. The Russian Army was lacking in officers, non-commissioned officers, transport and supply services, roads, and railways. He did not think that the Russians could concentrate more than these 40 divisions upon this frontier even up to the end of the first three months. Against these the Germans and Austrians could put 57 divisions. | ||

| MR. LLOYD GEORGE said that Austria would have to take precautions against Italy. | Influence of Austria-Hungary. | |

| GENERAL WILSON said that he had allowed 15 divisions for that purpose, and also 16 divisions to watch the Balkan States and in General Reserve. | ||

| MR. LLOYD GEORGE said that the weakness of the Russians was a surprise to him. In Manchuria, he understood that they put a 1,000,000 men into the field, and that the total of their soldiers numbered 3,000,000 or 4,000,000. | Weakness of the Russians. | |

| GENERAL WILSON said that Russia had only 78 divisions altogether, and of these she certainly could not concentrate more than forty he had said. Later on they might be able to bring up ten or fifteen others, but no more. | ||

| SIR WILLIAM NICHOLSON said that their great difficulty was their want of mobility. In Manchuria they were never able to leave the railway. | ||

| MR. LLOYD GEORGE enquired whether there would be any possibility of the Russians sending troops to France if we provided sea transport. | Possibility of transporting a Russian expedition by sea. | |

| SIR ARTHUR WILSON said that the transports could not pass through the Baltic. All the Navy could do would be to keep the Germans within the North Sea and the Baltic. | The Baltic impassable. | |

| MR. CHURCHILL asked whether there would be no chance of making terms with Turkey, and bringing Russian troops through the Dardanelles. | The Dardanelles. | |

| SIR WILLIAM NICHOLSON said that the Russians could not procure transport vehicles in France, and we were not able to provide them. | Russian Army deficient in transport. | |

| MR. CHURCHILL though that with our resources the difficulty might be surmounted. | ||

| THE PRIME MINISTER thought that the passage of the Dardanelles was an insuperable difficulty. SIR EDWARD GREY agreed. The Turks were in close relations with the Germans, and we certainly could not force the Dardanelles in those circumstances. |

The passage of the Dardanelles probably an insuperable difficulty. | |

| GENERAL WILSON said that the Russians were very frightened of the Germans, and even if other difficulties could be surmounted, he did not think the Russians would allow a single man to leave the country. The only arm of which the Russians had a surplus was cavalry—1,380 squadrons. He did not think the Germans would press their attack further than to pin the Russians down. | The Russians would not contemplate such an expedition in any case. | |

| The Committee adjourned. | ||

| On re-assembling— | ||

| LORD HALDANE asked if the War Office might assume that the Admiralty could arrange for the sea transport of the Expeditionary Force across the Channel within the time contemplated in the General Staff scheme. SIR ARTHUR WILSON said that he had not enquired into the matter, but he thought that the Admiralty could carry out this service without serious difficulty. THE PRIME MINISTER said that the Committee would now like to hear the views of the Admiralty. |

Serious difficulty in arranging for the transport of the Army in accordance with the General Staff scheme not anticipated by the Admiralty. | |

| SIR ARTHUR WILSON said that, from the naval point of view, the following considerations were important in an examination of the operations suggested by the General Staff:— 1. The effect upon public confidence in this country if the entire regular Army were dispatched abroad immediately upon the outbreak of war. There appeared to be a grave possibility of an outbreak of panic. This might result in the movements of the Fleet being circumscribed with serious effect upon our naval operations. 2. The consequences to the Navy of there being no regular troops in the United Kingdom to assist the Navy in defence matters. |

Effect of dispatch abroad of the entire regular Army upon public confidence and, consequently, upon the Navy. | |

| It was not a question of invasion by 70,000 men. The guarantee of the Navy against any number like that was absolute, but small raids might cause serious damage unless very promptly met. There would also be many points on the North Sea coast not now defenced which might acquire importance to the Navy in war, and for which the Army would be called upon to furnish protection. | Danger from small raids. | |

| 3. The consequences to the Navy of there being no regular troops available for direct co-operation in the naval operations. | Troops required for co-operation with the Navy in active operations. | |

| The policy of the Admiralty on the outbreak of war with Germany would be to blockade the whole of the German North Sea coast. The important portions of this were the estuaries of the Elbe, Weser, and Jade. | Naval plans for war. | |

| We could no foretell where the German Fleet would be on the outbreak of war. Normally the first division was at Wilhelmshaven and the remainder at Kiel. At the moment the whole was in the Baltic. The German Dreadnought class could not pass through the Kiel Canal at present, but the remainder of the Fleet could, and the enlargement of the canal was to be completed in 1915. Owing to the Kiel Canal we should also be compelled to watch the entrance to the Baltic. We had no wish to prevent the German Fleet from coming out, but unfortunately, if we left them free to do so, their destroyers and submarines could get out also, and their exit it was essential to prevent. If possible we should maintain our watch upon the German coast-line with destroyers. They would, however, be 300 miles away from any British base, so that none of them could remain very long at a time on the station, and consequently the number present at any one moment would be reduced. At night a few only would be necessary; more in the daytime. Outside the destroyers would be the scouts and cruisers, and on these the destroyers would retire when driven off by the enemy’s larger ships, whose own retirement would then, if possible, be intercepted. Engagements would constantly occur, and there would be losses upon both sides every night. How long this phase of the operations would continue depended upon the results of these minor actions. | Influence of the Kiel Canal upon naval operations. German light craft. Inability of destroyers to remain long on stations far from their base. Forecast of early operations. | |

| At the entrance to the Jade, which leads to Wilhelmshaven, lay Wangeroog. This island was now being fortified, and would be very inconvenient to our destroyers. It would also be of great value to the enemy as a signal station. Consequently its capture by us would be a great advantage. This would not be a difficult operation, as the attack could be supported by the fire of our ships at not more than 4,000 or 5,000 yards’ range, and the place could be easily held by a small force against recapture. | Jade Estuary. Wangeroog Island. | |

| During the nights the Germans would very probably wish to lay mines in the estuary of the Jade. This we should wish to prevent, and we could only do so effectually if we could seize and hold Schillinghorn. This place could be used as an advanced base, where our destroyers could lie in safety, if guns were landed. | Schillinghorn. | |

| Similarly there was a new fort at the entrance to the Weser on the way to Bremerhaven. The fire of the Fleet could knock that to pieces if desired, and another force might be landed there. | Weser Estuary. | |

| At Büsüm [Büsum], again a force might be landed to threaten the Kiel Canal. Small vessels could not get near enough to cover the landing with their fire. In this way, apart from the direct advantage to the Navy which would result from the capture of these signal stations and forts, &c., the German North Sea Coast would be kept in a state of constant alarm. Our force, having its transports close at hand, would be highly mobile, and could be landed and embarked again before superior forces could be assembled to destroy it. | Büsüm. | |

| If in this way we could retain the 10 German divisions of which General Wilson had spoken on the North Sea coast, we should make a material contribution to the ALlied cause by keeping these men not only from the theatre of war elsewhere, but from normal productive labour, possibly in dockyards or kindred industries. That meant that we should intensify the economic strain upon Germany. | ||

| For these operations we should probably require one division, perhaps more; later on we might even be obliged to try to destroy or drive out the German Fleet at Wilhelmshaven. It was not possible to say in advance how many men would be landed at each place. Troops for such enterprises must be good and have the best officers. | Troops required for the proposed naval operations. Wilhelmshaven. | |

| MR. CHURCHILL pointed out that the capture of Wilhelmshaven would involve regular siege operations. | ||

| SIR ARTHUR WILSON assented. Continuing, he said that it would be necessary to take Heligoland as soon as possible after the outbreak of war, and he proposed to carry out this operation with marines. He did not anticipate any difficulty. We knew what guns were there, and those we could easily fight. The only information as to the armament of which were were in need was as to the mortar batteries. As to the other operations, we could not foresee how much we could do; but the nature of the coast, with its numerous creeks and islands, providing shelter for the enemy’s torpedo craft, would make its blockade very arduous, and he would be very sorry if the Navy could count upon no regular troops to assist them in their operations. | Heligoland. | |

| SIR WILLIAM NICHOLSON point out that if the transports were kept close at hand they would be exposed to the danger of attack by submarines and destroyers, upon which danger Sir Arthur Wilson had laid so much stress in his published Memorandum⁕ of the 10th November, 1910, dealing with the possibility of an invasion of the United Kingdom. If, on the other hand, the transports were not kept close at hand, the mobility of the forces to be landed from them or re-embarked in them would be no greater than, if as great as, that of the enemy’s land forces, served as they would be by excellent railway communications. | Danger of attack upon the military transport ships. | |

| SIR ARTHUR WILSON said that the difference was that we should have command of the sea. The advantage which would lie with us in these operations was that we could hold two or three places as bridge-heads and reinforce whichever we wished. | ||

| SIR JOHN FRENCH said that the enemy would have equal facilities for concentrating overwhelming force secretly against any one of these points. | Ability of the Germans to concentrate overwhelming military force against any one point. | |

| SIR ARTHUR WILSON said that all the places he had mentioned were exposed to fire from seaward, which would enable the ships to support the troops. | Support from ships’ guns. | |

| MR. CHURCHILL said that that would appear to involve keeping the Fleet very close to the shore and would expose the ships to the fire of shore guns and torpedo attack. | ||

| SIR WILLIAM NICHOLSON said that it was, he understood, freely admitted that the ships could not remain close in shore at night, even if their fire would be effective; therefore, there was nothing to prevent the enemy attacking the detachments landed in overwhelming force and taking their positions with a rush, however well entrenched or defended they might be. As to the economic pressure, the Germans would mobilise these 10 divisions in any case. | Support from ships’ guns impossible at night. | |

|

The truth was that this class of operation possibly had some value a century ago, when land communications were indifferent, but now, when they were excellent, they were doomed to failure. Wherever we threatened to land the Germans would concentrate superior force. None of these places, so far as he could understand, had any essential importance for the naval operations. As to the fire of the guns of the Fleet, he thought its effect was overrated. It was difficult enough for field artillery, who were trained and armed for the purpose, to give support to other troops just where and when it was useful, the ships would find it hard to discriminate, even between friend and foe. |

The proposed joint operations impossible under modern conditions. Fire from ships’ guns not likely to be effective. | |

| MR. CHURCHILL pointed out that if the troops were dependent upon the guns of the Fleet, the Fleet would be tied to those troops. | Effect of landing troops upon naval mobility. | |

| SIR ARTHUR WILSON said that the ships would in any case be tied to the coast by the necessity for blockading it. | ||

| SIR JOHN FRENCH pointed out that horses could not be kept on board ship without very rapid loss of condition, and without horses neither guns nor troops could move. | Rapid deterioration of horses on board ship. | |

| SIR ARTHUR WILSON said that it would be infantry chiefly which would be required. | ||

| MR. CHURCHILL said that if we could capture and hold Cuxhaven, some advantage might be gained, but he did not imagine that we could do so. Any idea of besieging Wilhelmshaven was surely out of the question. | Cuxhaven. Siege of Wilhelmshaven out of the question. | |

| SIR WILLIAM NICHOLSON said that with our present military forces that was so, absolutely. Sir Arthur Wilson had referred to the example of the Japanese at Port Arthur, but for the siege of that fortress General Nogi had had 200,000 men and he was in addition entirely protected from any interference with his operations by a very large field army. Moreover, he lost 70,000 men before the place was captured. | Port Arthur. | |

| SIR ARTHUR WILSON, resuming, said that if these operations in the North Sea led to a successful Fleet action, it might subsequently become necessary for our Fleet to enter the Baltic and blockade the Prussian coast. We should then require bases for the Fleet in those waters, such as Fehmarn Island, to be captured and held. Further, such places as Swinemünde and Dantzic might be attacked. | Operations in the Baltic. Swinemünde. Dantzic. | |

| LORD HALDANE asked what we could do if we did capture Swinemünde? It would not cause the Germans a moment’s anxiety, for they had always ridiculed the idea of fortifying Berlin despite its comparative proximity to the sea. | Swinemünde. | |

| MR. CHURCHILL enquired whether our ships would not incur great risk by entering these narrow waters. | Risks in the Baltic. | |

| SIR ARTHUR WILSON said that great care would have to be exercised. Of course we did not know what attitude the Danes might adopt, but he imagined they would be neutral. In that case, he did not expect that the Germans would outrage their neutrality by laying mines in their waters and it was probable that we could get through. | Attitude of Denmark. | |

| MR. CHURCHILL enquired whether the Admiralty contemplated attacking Heligoland in any event immediately upon the outbreak of war, and whether it might not prove a very difficult and costly operation. | Heligoland. | |

| SIR ARTHUR WILSON said that such was his intention. He would rather not prophesy as to the cost. | ||

| SIR EDWARD GREY said that whatever military force was essential to the success of the naval operations should be made available for the purpose. | ||

| SIR ARTHUR WILSON said that the Admiralty considered that 1 division was essential. | Requirements of the Admiralty 1 division of regular troops. | |

| SIR WILLIAM NICHOLSON asked if the Admiralty would continue to press that view even if the General Staff expressed their considered opinion that the military operations in which it was proposed to employ this division were madness. | General Staff view of the proposed joint operations. | |

| SIR EDWARD GREY said that the problem which they had to solve was how to emply the Army so as to inflict the greatest possible amount of damage upon the Germans. So far as he could judge, the combined operations outlined were not essential to naval success, and the struggle on land would be the decisive one. SIR ARTHUR WILSON said that it was a question of degree. Any direct assistance which the Army could give would be valuable. |

The essential problem the most effective employment of the Army. The struggle on land decisive. | |

| SIR EDWARD GREY asked whether the Admiralty considered the capture and occupation of Schillinghorn was as an essential operation. | ||

| SIR ARTHUR WILSON said that it was not essential, but if it was not held by us the German cruisers could get out more easily, and the danger to our trade would be increased thereby. The Admiralty could not foresee what troops might be required, but they must press for some to be kept available. | Capture of Schillinghorn not essential. | |

| MR. CHURCHILL asked whether the very close blockade outlined and the landings of troops, with the consequent risking of ships in narrow waters and against forts, was essential to our strategy. | Danger of close blockade. | |

| SIR ARTHUR WILSON said that all the experience of recent manœuvres showed that close blockade was necessary. Any other policy would require a greatly increased number of destroyers. The safety of our Fleet depended upon preventing the German destroyers from getting out. He would add that the intention of the Admiralty to order this close blockade was one which it was absolutely essential to keep secret. It was not even known to the Fleet. The occupation of the places he had indicated would enable our destroyers to lie near to the shore. | Close blockade essential. | |

| SIR WILLIAM NICHOLSON said that to hold these places their garrisons must have guns. How were these to be landed. | Landing of guns. | |

| SIR ARTHUR WILSON said that, in addition to the cases in which troops would be required already enumerated, there would be those in which German destroyers might run into one of the many creeks for temporary shelter or repair, calling upon the local military authorities for protection. The protecting force would not be large, and a small military force at the disposal of the naval authorities for such a purpose would be valuable. | Other cases in which troops would be required to co-operate with the Navy. | |

| SIR WILLIAM NICHOLSON said that in view of the very large resources in men at the disposal of the Germans, he did not thibk that the assumption that these German protecting detachments would be small was warranted. | ||

| MR. CHURCHILL asked what was the least distance from the mouth of the Elbe to which our Fleet would approach. | ||

| SIR ARTHUR WILSON said that it depended upon whether it was desirable to let the enemy know the position of the Fleet or not. With wireless telegraphy the movement of the Fleet and transports could be easily controlled. Wireless communication was of more service to the hunter than to the hunted. | ||

| MR. CHURCHILL asked if it was of vital importance to keep the enemy’s destroyers shut in, and whether our Fleet would be unable to beat off an attack by torpedo craft at night. | ||

| SIR ARTHUR WILSON said that if destroyers knew the position of a Fleet accurately they were almost certain to meet with success at night. If a destroyer got within 3,000 yards of a battle-ship at night if [sic] could sink it. | Necessity for preventing hostile destroyers getting to sea. | |

| SIR WILLIAM NICHOLSON said that the creeks and islands all along this coast were so numerous that it seemed to him that nothing short of the occupation of the whole coast line by our troops would be of much service. | ||

| SIR ARTHUR WILSON said that if our combined operations retained 10 German divisions on this coast and away from the main theatre of war, we should accomplish a great deal. | ||

| THE PRIME MINISTER asked what the naval criticism of the proposals of the General Staff was. | ||

| SIR ARTHUR WILSON said that the Admiralty felt confident that troops would be required to second the efforts of the Navy, and also he did not know whether the number of troops which would remain in the United Kingdom after the departure of the 6 divisions was sufficient to insure that raids would be immediately overwhelmed. Moreover, in addition to the points already to be held on the east coast, others such as Great Yarmouth, Blyth, and Grimsby might be found to require military protection when war broke out. | Naval criticism on the proposals of the General Staff. Troops required to assist the Navy. Troops required for home defence. | |

| MR. MCKENNA said that the absence of the British Army from this country would, undoubtedly, have a great moral effect upon the English people, and there would be a great danger of interference with the freedom of action of the Fleet. There was no real danger of invasion, but many well-known officers and others had declared repeatedly throughout the country that we were not safe from invasion and there was, therefore, considerable risk of panic on the outbreak of war. That would result in great pressure being brought to bear upon the Government to tie the Fleet to the defence of our coast. The moral effect upon the English people would be so serious as to be disastrous. In addition the strain upon the Admiralty of having to provide the sea transport required by the Army immediately on the outbreak of war would, assuredly, hamper the initial operations of the Navy. | Moral effect upon the English of the absence of regular troops likely to be disastrous. | |

| THE PRIME MINISTER said that the Sub-Committee of 1908, which considered the question of oversea attack upon these islands, reported that—“in the event of an Expeditionary Force being dispatched for service abroad the Territorial Force should at once be embodied, and that at least two divisions of the Regular Army should remain in the United Kingdom until such time as the Territorial Force shall be considered fit to take the field.” | Sub-Committee of 1908 considered that Territorial Force should be embodied and 2 regular divisions retained. | |

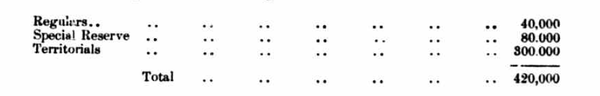

LORD HALDANE said that after six divisions had left the country the strength of the military forces would be— The Special Reserve Officers were provided for, but the Territorial Force was still wanting—1,600. |

Forces remaining in the United Kingdom after dispatch of the Expeditionary Force. | |

| THE PRIME MINISTER said that the point which the Committee had to settles was whether they were to depart from the conclusion come to in 1908, which he had just read. | ||

| SIR JOHN FRENCH said that the Territorial Force had made considerable progress in efficiency since 1908, and he considered that they would be able to deal with any attack which the Admiralty considered probable, certainly within a month of their embodiment. | Progress of the Territorial Force. | |

| MR. MCKENNA said that eminent Army officers expressed publicly a contrary opinion, moreover they were now discussing the proposal to denude the country of regular troops in the first week of war. | ||

| THE PRIME MINISTER said that the opinion of the Committee of 1908 was that—“Until at least four months had elapsed after the embodiment of the Territorial Force it would seem necessary to retain two division of Regular Troops fully mobilised in the United Kingdom.” | Sub-Committee of 1908 considered the 2 regular divisions should be retained for four months. | |

| MR. LLOYD GEORGE said that he had never been convinced that the retention of the two regular divisions at home was really necessary. | ||

| LORD HALDANE said that the Territorial Force had more Regular officers now than had been contemplated in 1908. | ||

| THE PRIME MINISTER said that the question raised was rather the ability of the Territorial Force to overwhelm small raids which had effected a landing on our shores than that of opposing invasion. | ||

| SIR JOHN FRENCH expressed his conviction that the Territorial Force would be quite able to deal with raids. They had a great advantage in their knowledge of the country. | Territorial Force quite able to deal with raids. | |

| MR. MCKENNA said that only as recently as the 24th March last he had, at the 109th meeting of the Committee, urged the reconsideration of the assumption that 70,000 men could possibly land upon these shores, with a view to the reduction of this figure. Lord Haldane and Mr. Churchill had then both opposed his suggestion. Now apparently the War Office had changed their minds. | Question of invasion. The limit of 70,000 men. | |

| LORD HALDANE said that that number had originally been agreed to as giving an “ample margin,” and he had no wish to withdraw from the view which he had expressed on the 24th March. | ||

| MR. CHURCHILL expressed agreement with Lord Haldane. Continuing, he inquired why the Admiralty thought that there was so much danger from raids in view of the very close blockade which it was proposed to maintain. | Danger of raids. | |

| SIR ARTHUR WILSON said that our blockading ships might be driven off temporarily. The whole German Fleet might come out. | ||

| MR. CHURCHILL said that he thought that was exactly what our Navy most desired. | ||

| (Major-General Sir Archibald Murray, Director of Military Training joined the Committee.) | ||

| LORD HALDANE enquired whether, assuming that invasion was impossible, and that raids need only be considered, it was necessary to our schemes for Home Defence—for which Sir Archibald Murray was responsible—that two regular divisions should be retained in this country. | ||

| SIR ARCHIBALD MURRAY said that he certainly did not consider their retention essential. As soon as the Territorial Force was embodied, it would join at its war stations, and move as required. It could be assembled centrally within three or four days. The only difficulty lay in the matter of horses, but even if there was a delay in completing mobilisation due to this cause, there were large numbers of cyclists who could be dispatched very rapidly to any threatened point on the east coast. | On the assumption that raids only are possible, the retention of 2 regular divisions for home defence is unnecessary. | |

| SIR ARTHUR WILSON said that the promptitude with which raids were countered was all important. The General Staff proposals involved replacing trained regulars by untrained Territorial troops. | ||

| THE PRIME MINISTER enquired when it was proposed to embark the troops for abroad. | ||

| GENERAL WILSON said that some troops would embark at noon on the second day of mobilisation, but the force proper would commence its embarkation on the evening of the fourth day, and complete it on the twelfth day. | Dates of embarkation. | |

| MR. MCKENNA said that if the assumption that our military plans for Home Defence must be based upon the possibility of invasion by an enemy not exceeding in strength 70,000 still held good, it would surely be most unwise to give the people of this country such cause for alarm that the movements of the Fleet would be paralysed. | Danger of the movements of the Fleet being paralysed by popular panic. | |

| MR. CHURCHILL enquired what the movements of the Fleet were, which the Admiralty apprehended might be paralysed. | ||

| MR. MCKENNA said that it might, for example, be necessary for the Fleet to withdraw from the North Sea, and move round the north of Scotland to the Channel. | Possible abandonment of the North Sea. | |

| THE PRIME MINISTER said that he supposed what the Admiralty feared was a popular demand that the Fleet should be retained within sight of our shores. | ||

| MR. MCKENNA assented, and instanced the effect of the popular panic on the Atlantic coast of the United States at the outbreak of the Spanish-American War. | ||

| MR. CHURCHILL said that he did not think the point as to the adherence of the General Staff to the figure of 70,000 men was an important one. The figure was admittedly a compromise between extreme views, and he had always understood that the Admiralty had up to now been overwhelmingly sure that invasion was out of the question. The point which the Committee had to settle was the most effective method of employing our military forces in the event contemplated. Some risks had to be taken in war. | Question of invasion. Limit of 70,000 men. | |

| LORD HALDANE referred to Sir Arthur Wilson’s Memorandum of the 19th November, 1910, which had been mentioned already:— “Even if he (the enemy succeeds in drawing off half our fleet, the other half, in conjunction with destroyers and submarines, would be quite sufficient to sink the greater part of the transports, even if supported by the strongest fleet which he could collect. The fleets would engage each other while the destroyers and submarines torpedoed the transports. |

Sir Arthur Wilson’s Memorandum on invasion. | |

| MR. MCKENNA expressed his agreement. | ||

| SIR WILLIAM NICHOLSON said that these arguments constituted an adequate criticism of the Admiralty proposals to land troops upon the German North Sea coast. While there was far greater certainty of our troops being overwhelmed by superior force should they succeed in effecting a landing. | Bearing of Sir Arthur Wilson’s Memorandum upon his present plans of operation. | |

| THE PRIME MINISTER said that the question which impressed him was, whether, supposing the whole of our 6 divisions had been sent abroad, we should have sufficient military force within the United Kingdom to overwhelm a serious raid. He agreed that the public would be nervous and would require to be reassured. Assuming that the Government decided to intervene on the Continent of Europe, it was obviously desirable that our intervention should be effective, but at the same time it was necessary to retain sufficient force in this country to meet all probable contingencies. What was the least force with which we could hope to intervene on the Continent effectively. | Necessity for crushing raids. Desirability of any intervention being effective. | |

| GENERAL WILSON said that the view of the General Staff was that our whole available strength should be concentrated at the decisive point, and that point they believed to be on the French frontier. The moral effect of sending 5 divisions would no doubt be almost as great as the dispatch of 6. | Concentration at the decisive point. | |

| SIR WILLIAM NICHOLSON said that from the military point of view it would be better to send 4 divisions than none. | ||

| SIR ARCHIBALD MURRAY said that he had no doubt whatever as to the ability of the troops detailed for home defence being able to deal with small raids. SIR JOHN FRENCH pointed out that if a raiding force once landed some mischief was bound to follow. The presence of the whole 6 divisions could not prevent that. |

No doubt as to the ability of troops allotted to home defence being able to deal with small raids. | |

| MR. MCKENNA said that he objected most strongly to the denudation of the country of all regular troops in the early days. | Objection to denuding the country of regular troops on the outbreak of war. | |

| SIR ARTHUR WILSON said that the Navy required at least one division to second its operations, and it was certain that many more troops would be required for our own coasts than could at present be foreseen. | ||

| LORD HALDANE said that in his view, if we had nothing to fear but small raids, the risk of denuding the country of regular troops could be taken. | ||

| THE PRIME MINISTER enquired as to the naval aspects of the proposal to transport reinforcements from India to Europe. Could they be brought direct, or would the Cape route have to be made use of? | Transport of troops from India. | |

| SIR ARTHUR WILSON said that he would prefer to bring them through the Suez Canal, but the necessities of the case could not be foreseen with any certainty. | ||

| SIR WILLIAM NICHOLSON pointed out that there were great objections to the Cape route, owing to its length and the consequent loss of condition which the voyage would entail upon horses and mules. | ||

| SIR ARTHUR WILSON, replying to enquiries, said that the Austrian Fleet though small was of good quality. In the last war the French laid up their ships and employed the crews on land. They might have to do so again. As a fighting force the French Navy had suffered from want of continuity of policy and from want of discipline, due to political interference. In Europe it was second only to the German Fleet, and it could easily defeat the Austrians. If possible he would like to bring our Mediterranean Fleet to home waters. | Austrian Fleet. French Fleet. | |

| MR. CHURCHILL asked how long it would take to bring reinforcements from India to Europe. SIR WILLIAM NICHOLSON said that two or three divisions might possibly be brought to Europe in three or four months. The delay was due to the difficulty of obtaining sufficient sea transport. |

Time required for transport of troops from India. | |

| SIR ARTHUR WILSON said that the transport and protection of these troops would involve the withdrawal of a great many ships from the trade routes. | Effect on the trade routes of this operation. | |

Footnotes

- ↑ The National Archives. CAB 38/19/49. pp. i-18.

- ↑ Steiner; Neilson. p. 214.

- ↑ Ibid.

- ↑ Morgan-Owen. p. 905.

Bibliography

- Morgan-Owen, David (August, 2015). “Cooked up in the Dinner Hour? Sir Arthur Wilson’s War Plan, Reconsidered.” English Historical Review. CXXX: 545. pp. 865-906. DOI:10.1093/ehr/cev158.

- Steiner, Zara S.; Neilson, Keith (2003). Britain and the Origins of the First World War. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan. ISBN 978-0-333-73467-4.